Eat Free or Die: Immigrant Foodways in New England

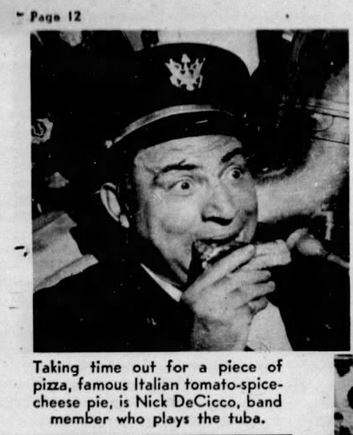

On October 1, 1950, the Boston Globe published an article on the feast of Saint Rosalia, the patron saint of Palermo. As the colorful and festive event unfolded in the Italian North End, a member of the processional band, the tuba player, was captured in a photo eating “a piece of pizza, famous Italian tomato-spice-cheese pie.”

Can you imagine a time when a newspaper needed to explain what pizza was? Can you even imagine America without pizza? Hard to fathom, right? And yet, at the turn of the twentieth-century members of the intelligentsia and the entrepreneurial world tried to solve the problem of poverty by changing the diet of the working classes. Researchers in the then nascent field of food science determined that the American working classes spent too much money and resources on food. If only they could teach them how to eat properly, they reasoned, the laboring classes would take better care of their attire and living conditions. These adjustments, it was believed, would improve their overall quality of life and could possibly alleviate fears of immigrant and popular uprisings.

Boston was central to this movement, this push to reform of the “foodways” of impoverished Americans. Among those, the newly arrived immigrants played a crucial role in representing poverty-stricken people with bad food, dress, and dwelling habits—with the added danger of harboring dangerous socialist ideas that could destabilize the nation. Hence, pizza and tomato sauce were not viewed favorably in the new era. Scholars have defined this period as the time of “Food Fights,”[1] when especially the food of the immigrants was seen as symptomatic of a broader social danger.

It was in this cultural context that Ellen Richards, the first woman scientist to graduate from MIT, together with Edward Atkins, a Boston businessman and member of the MIT Board of Trustees, collaborated on a project whose objective was to change the diets of impoverished Americans. Richards would become a faculty of Chemistry at MIT in 1884 and the first president of the American Home Economic Association, which was created to improve standards and quality of family life through a variety of educational and cooperative programs. The project would become known as the New England Kitchen. It rooted the teaching of a culinary science in public schools and colleges based on the culinary tradition of New England; that is, a rural and frugal cuisine to be embraced by the laboring classes.[2]

So, how did the major immigrant groups at the time react to these programs? Let’s imagine Chinese and Italian migrants—among the most numerous unskilled laborers that entered the United States between the end of the 1800s and the first few decades of the 1900s—and let’s imagine these groups learned from their children that their diets were wrong, unAmerican and somehow threatening. Those parents worked long hours in a country far away from their home countries, with different customs, which they had to learn to accept. At night, in the intimacy of their family, they wanted to share what they considered to be symbols of prosperity and well-being, rewards for the exhaustion of the day. Bolognese sauce over pasta, pork belly over rice; that was happiness, family and cultural survival.

There is a Chinese expression, directly linked to eating habits, that also emphasizes a sense of hardship and suffering. That is, chi ku (吃苦 – to eat bitterness). The verb chi expresses the act of eating and hence appropriating oneself with the bitter taste of life. Ku means bitterness and it is one of the five tastes recognized by the Chinese culinary tradition. Bitter is one of the specific sets of flavors that generate the complexity of savory experiences each mouth can expect when eating. Ku is also used to describe meager conditions one is currently living in or to refer to a past tribulations now overcome.

Similarly, Mangiare pane e cipolle (to eat bread and onions) is a common Italian expression to describe misery and deprivation. Often used to remember a time in the past when the economic conditions of an individual, a family or an entire community were depleted and poverty-stricken.

Chinese and Italian migrants who had landed on American shores at the end of the nineteenth century had surely eaten their share of bitterness (and bread and onions). But in the new world they had found more meat than they had ever seen in their countries of origin. The abundant, American production of food made it possible even for them to afford meat and other delicacies. Both groups knew what it meant to be able to eat well, their culinary traditions were imprinted in their collective memories. The difference now was that not only autocrats and land owners could eat sumptuously every day, they could too. They did not need to wait for the one time of the year (Chinese New Year or Christmas) to smell delicious fragrances and reach papillary satisfaction. Were they really going to eat New England’s baked beans and brown bread?

It is fascinating to look at food and the evolution of American foodways to gain a better understanding of this country—its charms and its idiosyncrasies. A recently published textbook on the three major cuisines of the world includes both Chinese and Italian cuisines (the third is Mexican cuisine). The author, a renowned food historian, describes how he carefully picked these three because: “These are the oldest on the planet, with the longest span of evolution, and arguably these have had the greatest impact on the world today. They also best illustrate the crucial role of food in our cultural and social development.”[3] And in referring to the three cuisines together the author continues to explain that they “progressed through a long and fascinating series of events, witnessed the growth of empires and invasions, and has interacted with its neighbors, particularly in trade for the acquisition of raw materials. And each, of course, endures to this day in the form of a highly complex and sophisticated culinary tradition. Each is also the epitome of a world cuisine, being linked to an enduring civilization and in turn having a major impact on cooking around the world.” In fact, Chinese, Italian and Mexican are picked as representative world cuisine—the New England cuisine would be considered a regional cuisine— as “A world cuisine also tends to be dynamic and ever changing, easily adapting to and borrowing from neighbors and even farther-flung cultures in ever-widening geographic circles through the centuries. These may have originated as regional cuisines but eventually expanded on a national, continental, and then global scale.”[4]

American

scientists, a century ago, tried to push the New England Kitchen as the ideal

model for those who aspired to be healthy and prosperous. Young women were

educated in civics in public schools and through Home Economics programs where they

learned to eat the ‘right way’ to be truly American. The New England Kitchen project

failed and, as Donna Gabaccia argues, after the Depression and WWII, Americans

started to become more curious and adventurous. They wondered what their

neighbors were cooking in their pots. Luckily, we can now enjoy pizza, Peking

duck and even possibly a fusion of the two.

[1] Gabaccia, Donna, We Are What We Eat. Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), p. 122.

[2] Levenstein, Harvey, Revolution at the Table. The Transformation of the American Diet (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

[3] Albala, Ken, Three World Cuisines: Italian, Mexican, Chinese (Lanham: AltaMira Press, 2012).

[4] Albala, Ken, Three World Cuisines: Italian, Mexican, Chinese (Lanham: AltaMira Press, 2012), p. 69-70.

About Insights

About Insights

About Emmanuel

About Emmanuel